Lightning Safety: Debunking the Myths

There are certain things in life we all instinctively know it’s best not to mess around with – bears, poisonous snakes, fast-moving vehicles, and beehives are just a few. Somewhere very near the top of that list, I’m sure, most hikers who’ve ever been caught outside in a thunderstorm would add lightning, that always awe-inspiring natural light show that is oh-so-impressive from afar but oh-so-scary when anything even remotely close.

To put it bluntly, lightning is a killer and a pant-filler for even the most fearless of backcountry “badasses”. But that doesn’t mean we’re totally helpless when it comes to protecting ourselves from it – hiking or backpacking safety should always be our number one priority.

There are lots of myths and misconceptions about lightening strikes on outings in the outdoors. And a lot of confusion regarding what course of action to take when caught in a storm or following a strike. In this article, I aim to clear up these myths with a little bit of debunking and a few thunderstorm safety tips when danger is brewing above.

Before that, let’s start off with a few of the most important lightning safety tips.

- Pay close attention to weather forecasts

- Stay home if there is any risk of a thunderstorm

- Take cover as soon as you see a storm approaching

- Move calmly to safety to reduce secondary risks (i.e. trips and falls)

- Stay away from exposed areas (ridges, meadows, summits)

- Learn how to treat victims of lightning strikes

- Take shelter in caves or under isolated trees

- Huddle together when a storm is approaching

- Be afraid to turn back if a storm is brewing

Lightning Storms for Dummies

We’ve all seen one before, but do we really know what causes them? Below, we’ve added a few of the basics to help you understand the ins and outs of lightning strikes.

What Exactly is a Lightning Storm? Is Thunder Dangerous?

In short, a lightning strike is an electric discharge between the atmosphere and an object on the earth’s surface.

You may also be interested in our other articles on health, hygiene & survival:

- A phobia of bears? Getting Lost? Being alone? Don’t let fear get the better of you with our guide to beat it.

- Our wilderness survival guide will prepare you for nearly anything mother nature has to throw at you.

- Simply owning a cathole trowel doesn’t mean you’re complying with LNT. Learn the correct way “to go” in the woods.

- While we do recommend wilderness medical training, some simple knowledge can help you through when in a bind.

In more precise scientific terms, the National Severe Storms Laboratory describes lightning as follows:

“Lightning is a giant spark of electricity in the atmosphere between clouds, the air, or the ground. In the early stages of development, air acts as an insulator between the positive and negative charges in the cloud and between the cloud and the ground. When the opposite charges builds up enough, this insulating capacity of the air breaks down and there is a rapid discharge of electricity that we know as lightning. The flash of lightning temporarily equalizes the charged regions in the atmosphere until the opposite charges build up again.”

NATIONAL SEVERE STORMS LABORATORY

Why are Thunderstorms Dangerous?

According to National Geographic, lightning strikes are one of the leading causes of weather-related injuries and death in the United States.

But what’s responsible for their capacity for harm?

Let’s look at a few stats:

- Lightning is a giant discharge of electricity that can contain up to one billion electrical volts (for reference, a standard 100-volt power outlet can kill an adult human)

- Lightning bolts can strike objects over 15 miles away, even when there are no clouds directly overhead

- A lightning bolt can raise the air temperature by as much as 50,000 degrees Fahrenheit

- Being struck by lightning can result in cardiac arrest, brain damage, memory loss, psychological changes, and various other long-term injuries

- Lightning strikes do not only occur in thunderstorms, but also in volcanic eruptions, snowstorms, forest fires, and hurricanes

Types of Lightning Strike

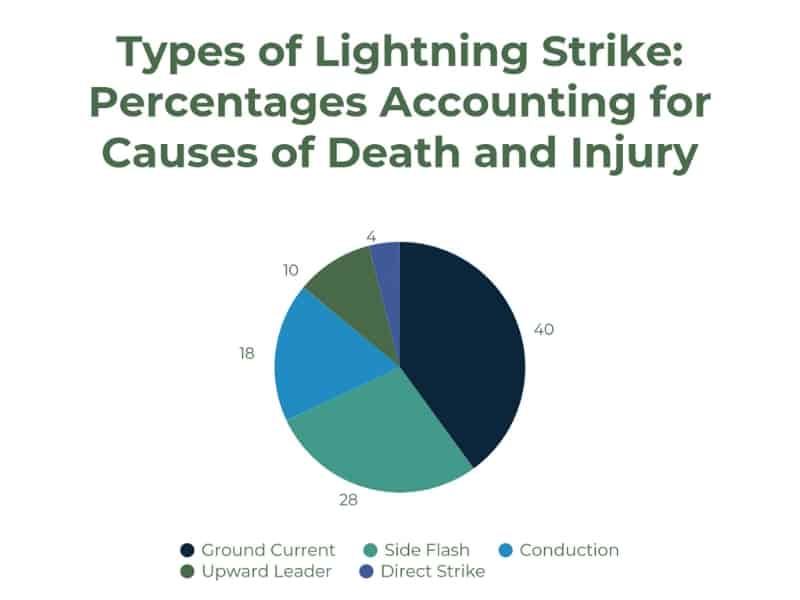

The two main types of lighting strike are direct strikes and side flashes, but lightning-related injuries can also be caused by conduction, ground current, and upward leader strikes:

Direct strike

As you might have guessed from the name, this type of strike involves a direct hit on the victim. While most of us are apt to believe this is the standard form of lethal strike, direct strikes are in fact very uncommon (accounting for only 3-5% of all deaths and injuries) and usually only happen when the strike victim is in very open, exposed terrain.

Side flash

With this type of strike, lightning bolts first strike a tall object (like a tree), and, instead of following the object to the ground, arc or jump sideways to objects that pose less resistance – like people standing nearby. This kind of strike accounts for about a third of injuries and fatalities.

Conduction

As the name suggests, this type of strike occurs when lightning is conducted from the original strike point to its victim. Many things can conduct lightning over relatively large distances, but the most common are fencing, plumbing, metal surfaces, and phone lines.

Ground Current

When lightning strikes any object in exposed terrain, a great deal of its energy then travels outward along the surface of the surrounding terrain, creating what is known as “ground current.” Because ground current can cover a far larger area than a direct strike or a side flash, it is the most common cause of lightning-related deaths and injuries, accounting for 40-50% of the total.

Upward Leader

Also known as a “streamer,” this type of strike accounts for about 10% of human injuries. In this case, hikers are missed by the lightning’s main flash but are caught by connecting upward discharges from the earth’s surface, i.e. the upward leader. Although upward leaders carry far less charge than the main stroke or flash, they are still powerful enough to cause injury or death.

Common Myths: Debunking the “Fake News” About Lightning Strikes

Lighting strikes have about as many myths surrounding them as your average presidential assassination or Greek history book. None of these myths are helpful and in most cases only add to the chances of us not taking the dangers posed by lightning seriously enough.

× Myth: Lightning never strikes twice in the same place.

√ Fact: Lightning can and often does strike in the same place twice, most notably exposed, isolated and tall features in the landscape. The Empire State Building, for example, is struck 23 times per year on average.

× Myth: The odds of being struck by lightning are one in a million.

√ Fact: How many people get struck by lightning each year? The odds of being struck by lightning in the U.S. are 1 in 700,000 in any given year. Over the average lifetime, these odds drop to 1 in 3,000.

× Myth: You are safe indoors.

√ Fact: about a third of all lightning-related injuries occur indoors, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Lightning can enter buildings through phone lines, electrical cords, electrical appliances, metal door, and window frames, and even the plumbing.

× Myth: Lightning victims retain an electrical charge that makes it unsafe to treat them for lightning-related injuries.

√ Fact: No current will flow from the victim to the rescuer following a lightning strike.

× Myth: Rubber shoes will protect you from lightning.

√ Fact: According to Ready.gov, rubber-soled shoes will do little, if anything, to protect you from a lightning strike.

How to be Safe on a Hike when Lightning Storms are Brewing

Let’s start with the bottom line:

There is no place that is absolutely safe during an electrical storm.

In any given year, people are struck in city streets, wide open spaces, through windows at home, in their cars, in mountain huts, on boats, and in many other ostensibly sheltered locations.

Now that we’ve got that out of the way, let’s look at some proactive lightning safety rules you can take to minimize your chance of becoming a statistic.

Preparation and Prevention

As with any aspect of safety in the outdoors, prevention of injury or death begins at home. Before heading out on any trip, take the following steps:

- Check at least three weather reports to gauge the likelihood of an electrical storm. If the chance of thunder & lightning happens to be higher than 10%, we’d highly recommend staying put and rescheduling your trip for another time.

- Identify potential shelters on your route and mark them on your map.

- Have an emergency plan in place for yourself and your group.

- If you are headed into an area renowned for sudden changes in weather and prone to afternoon thunderstorms (common in mountainous areas in summer months) be sure to set off early and give yourself at least a two-hour buffer to arrive at the next sheltered location.

Don’t get caught out by mother nature, learn how to protect yourself with our guides:

- How many leaves does poison oak have? Not sure, then check out our guide.

- Bear protection can take many forms starting with avoidance. Learn more in our bear safety guide.

- The little suckers getting the best of you? Learn campsite mosquito control.

- Follow our practical steps to tick bite prevention 101.

What to Do During a Thunderstorm

Most of us who have spent a lot of time in the backcountry have had a lightning storm sneak up on us unexpectedly. In such cases, how do we know when we’re in trouble?

You can estimate the distance to a lightning strike by counting the seconds between the lightning flash and the thunder that follows (“one Mississippi, two Mississippi,” etc.). Divide the number of seconds by five and this will give you the approximate distance to the actual lightning strikes.

Studies have shown that a second strike can occur 6 to 8 miles away from the first strike. Therefore, when the time between the strike and the thunder is less than 40 seconds you could be in danger if the storm is moving towards you and will need to take action quickly.

Taking Action: The Steps to Take When a Lighting Storm is Headed Your Way

Seek Protection

More than half of all lightning injuries and fatalities occur when lighting hits the ground near where hikers are standing or taking shelter. The electrical current runs through the ground to nearby objects (i.e. hikers) that act as conductors to receive the charge. This results in burns on the body, and, in extreme cases, death.

When thunder roars, go indoors – A house or other substantial building offers the best protection from lightning because, in most cases, such buildings will contain some form of mechanism that will conduct the electrical current from the point of contact to the ground.

Unless specifically designed to be lightning safe, small structures do little, if anything, to protect occupants from lightning. Many small open shelters on popular hiking trails that are designed to provide some respite from the rain and sun will offer no protection against lightning and, therefore, should be avoided during thunderstorms.

During one especially terrible storm at the Griswold Scout Reservation in New Hampshire, 23 Scouts who had taken shelter under a canopy were hospitalized after lightning struck close to the canopy.

If there is no building in which you can safely take shelter, here are a few safety procedures to minimize the risk of being struck.

- Separate and, if possible, find cover under clumps of shrubs or trees of uniform height

- Always, spread out 25′ to 30′ from each other, but maintain voice contact

- Stay off ridges and exposed passes – you are typically better off at lower elevations

- Stay out of broad open areas like meadows or lakes

- Do not try to take shelter in a cave

- Stay away from water

- Avoid single high trees (do not set up your tents near them either!)

Assume the position

If you are caught on exposed ground with no possibility of taking shelter when a thunderstorm arrives, the key to minimizing the risk of being struck by lightning is to make yourself as small as possible.

Here’s how to do so:

Crouch down with feet and knees together, chest on knees, head tucked down, with your hands covering your ears and eyes closed.

This position not only minimizes your exposure but will encourage any strike to pass down your back, hopefully without damaging your vital organs. Covering your ears and closing your eyes will also protect them from the loud noise and intense flashes of light from nearby strikes.

Further Preventative Measures: Don’t Make Yourself a Target

- Ditch your trekking poles and any other metallic or electronic objects that may attract the lightning to you – metal objects in the victim’s pockets (like smartphones) can concentrate the charge and make the injury even worse

- Discard any jewelry

- Distance yourself from your pack and the metallic objects by at least 100ft

- Lightning will often strike the tallest object in the area, so don’t stand next to a single tall tree or rock during a thunderstorm

- If taking shelter in a mountain hut, avoid contact with plumbing (don’t wash your hands, shower, or drink from faucets) and electrical appliances (lightning can travel long distances in both phone and electrical wires)

- Do not, under any circumstances be tempted to use your phone, even to call for help

What to Do if Lightning Strikes a Member of Your Team

While I seriously hope that none of our readers ever need to use the following advice, knowing what to do in the event of a member of your group being struck by lightning is crucial.

We may instinctively believe that anyone struck by lighting is done for, but every year hundreds of people struck by lightning live to tell the tale. After any strike, our immediate attention may be the difference between life and death for the victim.

Simply put, to be struck by lightning is to be the recipient of a very severe electric shock. As with any electric shock, the first aid required post-strike is very similar to the first aid required to treat burns and cardiac arrest (consider getting WFA certification).

The basic procedure you should follow in the aftermath of a nearby strike goes as follows:

- Do a quick headcount to ensure everyone is still present, asking all of the dispersed members of your group to respond to your calls

- If any team member fails to respond, go to them only when it is safe to do so, and, importantly, alone – further strikes may occur and grouping together at this stage could endanger everyone in the group by creating a larger target

- Give priority to any victims who are not breathing and begin CPR immediately

- Check for and give first aid for burns – in lighting strikes the worst affected areas are commonly where the strike victim has worn jewelry and on the fingers and toes

- Treat the victims for shock, laying them down with their head slightly lower than the legs and torso and covering them with an emergency blanket

- Call for help only when you are sure the risk of another strike has passed

For more lightning information, particularly on how to stay safe during a thunderstorm check out NOAA Lightning page or the National Lightning Safety Institute.

When upgrading your packing list with new equipment, don’t forget to check out the following articles:

- We reviewed several models before deciding on the best hatchet for backpacking

- With modern synthetic materials, camping towels are now lightweight and fast drying

- Our multi tool reviews breakdown which tools are best for those small jobs

- A folding camp saw can be useful for those who want to collect (and prepare their own firewood.

To be struck by a lightning is very scary! I wouldn’t wish that. Thanks for this blog, very insightful.